Hotel Marcel

Hotel Marcel, New Haven

Faith and I didn’t travel this year, what with the new house and setting up the workshop. There were some adventurous plans, but life was like No, not happening.

We like visiting and revisiting cities: New Orleans, Houston, Galveston, Cincinnati, San Diego, Los Angeles, DC, Detroit. Those have been some of our favorites over the last few years (Cincy was a surprise entry on that list). We want to visit Seoul someday, where Faith’s family is from, and I’d like to revisit other parts of Europe that I haven’t seen yet. I love train trips. Like other places (Asia, Africa), Europe has some baller trains. But besides the expense, there’s the issue of our two trauma dogs, my absolute disdain for air travel, and the fact that we’re addicted to that frigging workshop. Another Grey’s Anatomy joke floating around our household (see the post about “hanging a shingle”) is when I wake up and say to Faith, who is half-asleep, that I need to cut. I want to cut. I HAVE to cut. Meaning, I’m heading to the barn.

Three things we like to do when we visit cities:

Bikeshare rides. It’s the best way to get around and actually take in a city. As a cycling nerd, I used to be iffy about e-bikes. But when a city’s bikeshare has e-bikes, I’m all over it. Those things are fun.

NBA games. I grew up on the game, playing and watching it, and Faith somehow got on board. I have no idea whether it’s real or not, but Faith’s willingness—and sometimes enthusiasm—to watch basketball with me seems genuine and is ridiculously fun. We’ve attended live games in New Orleans (against my hometown Houston Rockets) and in Detroit (against my beloved San Antonio Spurs). Coming up, we’re headed to Brooklyn to watch them play the Spurs again. It’s our version of splurging. A Spurs Splurge. (Cue Faith’s disgusted look at my corniness, followed by a deflated-pitched “oh my goddddddd,” followed by “That was actually pretty good” and reluctant laughter.) Faith likes it when they shoot t-shirts into the crowd out of a cannon during halftime. And spin moves.

And finally, hotels. We love them. Ninety percent of the time we need to stay in a hotel, it’s at a Best Western because I’m a rewards member, and they offer a notoriously not-bad complimentary breakfast, which usually includes waffles, which Faith has an obsession with. But only Best Western Plus, which I affectionately refer to as Best Western Pleu. Pleu is spelled plus in French, too, but pronounced like pleu, i.e., ever so slightly extra fancy in my rendering (Faith reminds me that I first made this joke at the BW+ in New Orleans, whose French and Creole culture made it extra funny, and whose BW+ is exceptionally, almost shockingly pleu). Occasionally, though, we hit those trendy hotels—the ones with late-night bars, indirect lighting everywhere, cool suites, elegant architecture, and seriously good brunches: Bloody Marys, eggs Benedict, cheesy shrimp and grits, etc. We dabble in bougieness.

That is why, a few nights ago, to celebrate an anniversary, we decided to do something less expensive and time-consuming than a full-on getaway and slightly more than a staycation, although technically, I suppose it might have been one since it’s practically in our backyard. We spent the night at Hotel Marcel, exactly 2.4 miles away. Had the weather not been so tropical-stormy that day, we would have ridden our bikes. New Haven’s “Long Wharf,” where the hotel is, is lined with food trucks, mostly serving Latin American food. The street tacos we got were insanely good, and insanely hot. It was excellent. We ate them in our room overlooking the New Haven Harbor.

In the 1950s and 60s, New Haven attracted modernist architectural superstars to give the city a makeover. Some of them taught at and headed the Yale School of Architecture, designing buildings for the city during their tenure here. As a result, New Haven has some weirdly good-looking fire stations and parking garages. Several of the “modernist” buildings in New Haven are borderline or even full-on postmodern. Robert Venturi, a pomo architecture pioneer, designed one of the fire stations. Eero Saarinen, who designed the St. Louis Arch and the swooping Dulles airport in DC, and the also-swooping TWA terminal at JFK in NYC, brought his signature swoop to Yale’s hockey rink, affectionately known here as the Yale Whale (see my first post about ECW’s origin story to learn about our semi-personal connection to Saarinen).

From left: Venturi’s fire station and Saarinen’s Ingalls Rink in New Haven; Saarinen’s terminals at Dulles & JFK.

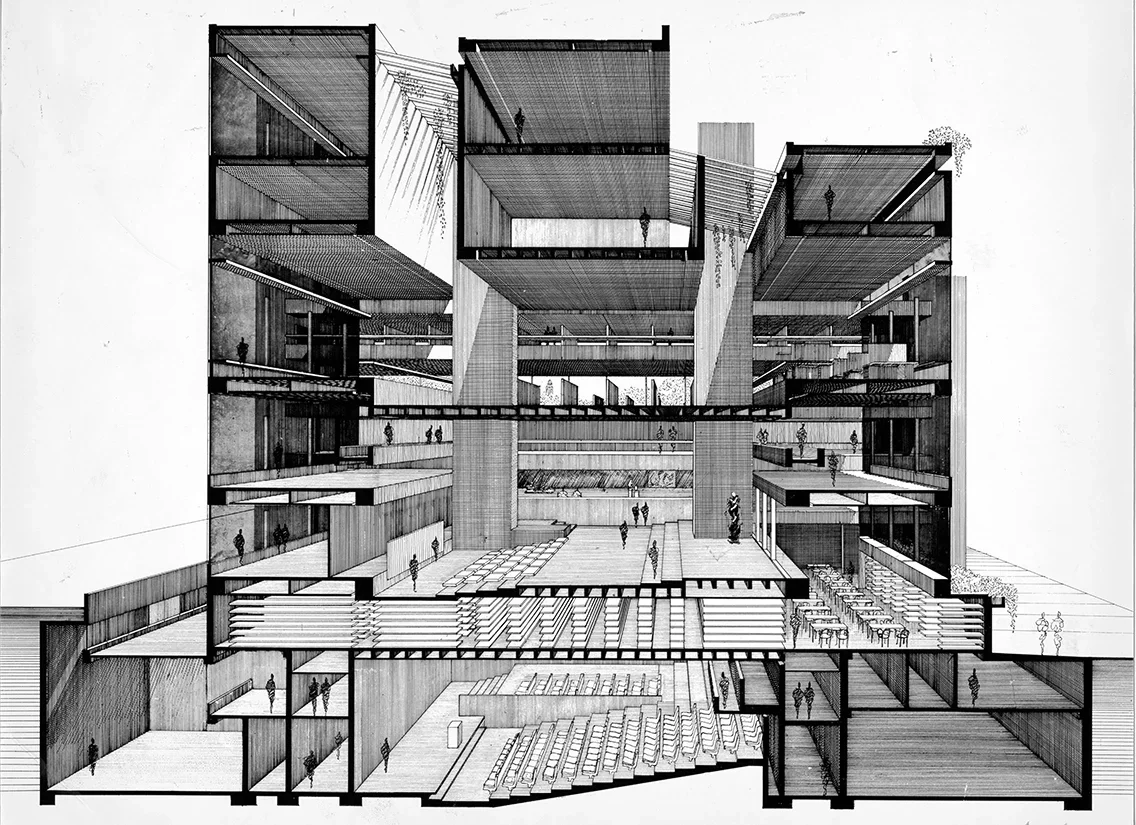

As brutalism began trending in the 1960s, New Haven was all in. One of its chief advocates and then-president of the architecture school, Paul Rudolph, designed the school’s building, a downtown parking garage, and Crawford Tower, a low-income apartment building whose balconies look like buckets to me. Brutalism doesn’t exactly mean what it suggests in English, though most folks would say that about it. It’s about the use of raw, often unfinished materials, usually concrete. At least that’s the case for the examples of Brutalism here (it has a longer history and greater diversity of styles that I won’t rattle on about).

Rudolph’s Crawford Towers; Saarinen’s Stiles College at Yale; Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage.

You have to touch a Brutalist building and go inside one to get the best sense of it. They’re often scratchy, like 10-grit sandpaper, almost as if they were rough-chiseled instead of using forms. The interiors tend not to enclose anything, unlike when we use drywall in houses to cover the framing, wiring, and plumbing. They aren’t statements so much as expressions of some principled dedication to stripping things down to their bare necessity. Touring Rudolph’s architecture school building with one of its faculty members, I understood much better how he, too, was bridging the modern/pomo divide, reintroducing ornamentation and symbolism, resisting symmetry—the kinds of things the pure modernists detested. In my time in New Haven, I’ve learned not to judge a building by its cover. The Yale Whale is a perfect case in point. Looks funny on the outside, but it transfixes you on the inside.

Paul Rudolph’s Yale School of Architecture.

On the other hand, the city was definitely asking Marcel Breuer to design a statement piece when it approved the Armstrong Rubber Company’s plan to construct a building alongside I-95 in the Long Wharf district. Like a lot of cities, New Haven was, at that time, doing something it and other cities later came to regret: rebuilding itself around cars. Interestingly, it was widely referred to as urban “revitalization.” The Armstrong building was basically going to be a giant billboard that reads, “New Haven is a Modern City.”

It did, in fact, become a billboard. It was sold to another tire company, Pirelli, and remained vacant from the 1990s to the 2010s (I attended an art show staged on the bottom floor during the vacancy years), during which time IKEA moved in next to it, demolished part of it for extra parking, and used the rest to hang a giant IKEA sign for drivers to see from the highway.

The irony of this should not be lost on anyone. IKEA sells knockoffs of classic mid-century modern furniture (first to mind are their versions of Saarinen’s Tulip series of chairs and tables), and, I would personally say, desecrated what is actually a fascinating piece of MCM history. The Armstrong building is a superb example of Brutalist architecture, and it’s sort of mind-boggling because of how it’s cantilevered. I can’t describe it; there are photos for you to see for yourself. But besides the cantilever magic trick he pulled off, the beveled windows are so dang neat. They’re neato. They reduce me to childhood vocab-ways of thinking because they’re that cool. Fortunately, others agreed. Marcel Breuer’s building became Hotel Marcel in 2022.

From Left, top: an art show held during the vacancy years; a closeup of the neato bevels; destruction of part of the building to make parking space for IKEA; the shuttered building.

From left, bottom: Closeup of Breuer’s Brutalist use of concrete; IKEA store edge and banner pasted on the Armstrong building’s sign; IKEA ad on the building; the Breuer building reflected in the windows of IKEA.

A few of the original interior materials and pieces remain, but not much. Still, the design firm did a helluva job staying true to Breuer’s aesthetic, down to the furniture in the rooms, which includes his Cesca Chairs. As I said in some other post, not sure which one, I’m cane-curious. I’d like to try using it. The Cesca Chairs aren’t in my top five list of chairs, but it was still fun to see them in a hotel room.

Marcel Breuer’s Cesca Chair

It was not uncommon for modernist architects to design furniture, going back to Le Corbusier’s iconic lounge chairs and the Bauhaus’s commitment to the intrinsic interdisciplinarity of the arts, crafts, and trades. Breuer is probably more famous for his Wassily Chair than the Cesca, named after his Bauhaus colleague Wassily Kandinsky.

Trigger warning for the nerd-averse reader: I’m about to name-drop a bunch of chairs. But trust me, you do know these chairs, which is why I’m including pics below.

Some of the most iconic MCM chairs are testaments to the influence of one Florence Knoll, whose name is associated with one of the two main manufacturers of MCM furniture, the other being Hermann Miller. They’re still the main ones, by the way; it’s just that in this age of venture capital buyouts and mergers and whatnot, the org chart is different. They’ve been bought and morphed into a mashup parent company called KnollMiller, which also owns the only place I know of in the US where you can buy authentic MCM designer furniture: Design Within Reach. I only know this because a kind customer service lady explained it to me on the phone the other day while helping me order a replacement part.

Mostly male architects changed the exteriors of buildings, but Florence is largely responsible for changing the interiors, including furniture. She was virtually raised by the Saarinen family, who ran an art school she attended, and was extremely close to their son Eero, who was like a brother to her. She’s the one who urged him to design the engulfing Saarinen Womb Chair. Knoll apprenticed with Walter Gropius, who had previously founded and directed the Bauhaus, and with Marcel Breuer. Through Eero, she met and worked on furniture designs with Charles Eames, whose bent plywood and leather-cushioned lounge chair and ottoman are among the most recognizable MCM design objects. I mean, it’s up there.

From Left: Eero Saarinen’s Womb Chair; the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman

Knoll looked to artists as well, nudging them to think about furniture. She’s why the sculptor Harry Bertoia designed the wire mesh Diamond Chair, and why Isamu Noguchi (also a sculptor) designed the cyclone table with its twisted metal base (not a chair, and don’t recommend sitting on it, but still). She persuaded another former teacher and MCM giant, Mies van der Rohe, to give Knoll the rights to produce his Barcelona Chair, a cushioned leather chair and ottoman with a curvy X-shaped base.

Harry Bertoia’s Diamond Chair; Isamu Noguchi’s Cyclone Table; Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair.

Like me, Florence Knoll was a chair nut, and I love her for that. The most utilitarian of all objects has been reimagined in so many ways that it has turned into an art form. My favorite thing to do at art museums is look at their chairs—not the ones in the foyer or lobby, but the ones on display.

Knoll understood that chairs and furniture in general help structure how we live and work, and how we socialize with each other. It’s true she was focused more on office design. She probably single-handedly invented the look of modern office spaces. Her “Knoll Planning Unit” (that’s a funny name to me, but she was trying to take the gendered edge off of interior design) designed offices for IBM, General Motors, CBS, and stuff like that. In lesser hands, they go too far into bland territory, but not her. Like the Eamses and others, she insisted on blending a clean aesthetic with organic colors and textures. And the emphasis she placed on collaboration is transferable to any space where we spend a lot of time together with people, or where we want to get comfortable and relax.

Hotel Marcel achieved that. They nailed it. Bravo.