MCM At Its Best

MCM. Mid-Century Modern. What is it, why do we love it, and how do we approach it?

I started building shaker furniture when I was younger because I was raised on PBS, and Norm Abram was effectively my first woodworking teacher in his role on The New Yankee Workshop. I watched the show and studied his books like a bible. The first projects I can remember making are a bookcase, a cradle for when my first kid was born, a raised-panel toybox for when my second kid was born, an entertainment center for a friend, and a classic shaker-style nightstand with tapered legs.

Carpentry runs in my family. My grandfather built houses, and my dad and uncle helped as kids and teenagers. One cousin is now a contractor in Houston, building upscale homes (I would never call them McMansions, because he’s thoughtful about his work, but they’re incredibly big and beautiful houses like the one the Sopranos had on maybe the best TV show ever). I inherited some of my dad’s tools, including a jigsaw and a power drill that don’t work now but look great, like some art deco, industrial pieces of metal sculpture. I use his equally art deco-industrial-looking miter gauge on my Dewalt jobsite table saw, both for nostalgia and because it feels like it was made from granite, whereas the stock miter gauges that come with even the fanciest table saws today are flimsy pieces of junk.

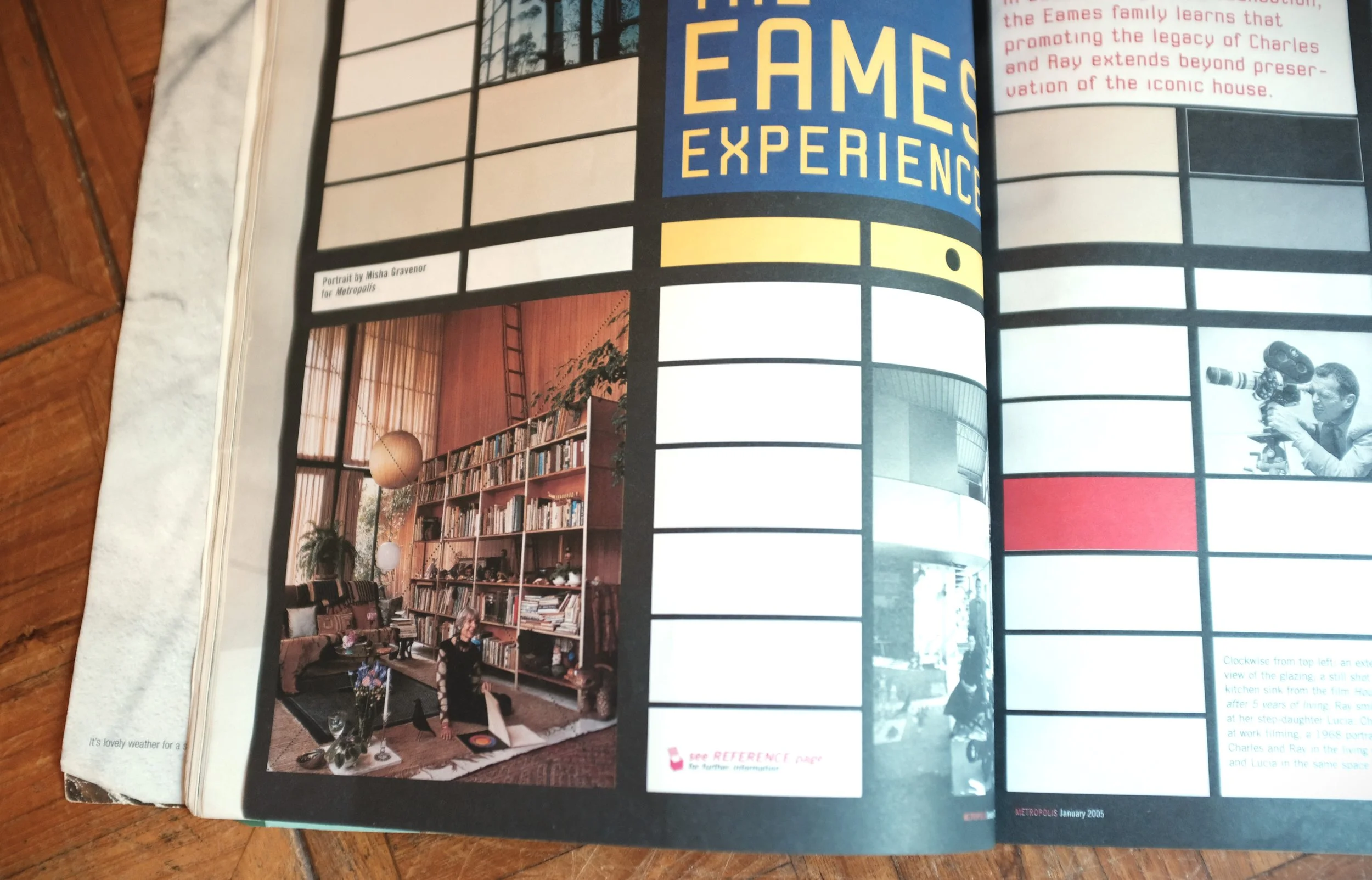

Somewhere along the way, I came across an issue of Metropolis Magazine that featured the designs and lives of Charles and Ray Eames. I think I was at a newsstand on Chapel Street in New Haven that no longer exists when I saw it and bought it. I had just purchased my first house, a mid-century ranch, and was spending a lot of time thinking about how to furnish it in a way that was true to its 1950s origins. I wanted something sleek and minimalist, but not cold and impersonal. On the cover of this magazine, which I’ve had for so long now and spent such a great deal of time with that its edges are worn, I saw something that, and I’m not kidding here, changed my life in no small way.

The style of Charles and Ray Eames is both the definition and the exception to the rule of MCM because of how they meld minimalism and utility with organic textures and a sense that the pieces they design and the spaces they build are actually meant to be lived in. They were also, it should be noted, a pretty cool couple (see them on a motorcycle below, with Charles, the wife, doing the driving).

I’m not quite sure how to describe or explain it. They lit a fire in me both in terms of my taste and intellectually. In my day job, I’m an academic. I later wrote a book (after publishing several articles in preparation for it) about “dwelling,” which was published in the Architecture and the City series of Columbia University Press. As I was writing it, I had no idea that the main audience would be architects and designers. I’m a philosopher. I thought I was doing philosophy. In hindsight, it’s not so surprising that I landed in a place of thinking about the meaning of homes, housing, and lifebuilding, all the way down to the level of design.

Mid-century modern design has had a complicated afterlife. IKEA made it affordable to the masses, which is not a disservice since one of the original aims of the Bauhaus and many MCM designers and architects was to do just that, but that’s not what happened. Design Within Reach, Herman Miller, and Knoll still sell original MCM furniture today, and it’s incredibly expensive - not “in reach” for most of us. That’s the supreme irony of MCM. It began as design for the people, for workers, marshalling mass production to make well-designed objects and furniture available to everyone. At some point, let’s say the 1950s and ‘60s, it was assimilated by a corporate aesthetic. It was no longer accessible to most people except in uncomfortable situations like doctors’ visits and loan application interviews at banks.

Some of them resisted in small ways. Eero Saarinen, who worked with the Eameses, only agreed to do public and university projects - the St. Louis Arch, DC’s swooping TWA Terminal at Dulles Airport, and the “Yale Whale” hockey arena here in New Haven. His famous Tulip Chair will run you $600 or so today. The Womb Chair is $ 1,100, and the Tulip Tables are even more expensive. The beloved Eames Lounge Chair will set you back six grand at Design Within Reach (ironic case in point).

To me, that’s not the only bad thing to have befallen the MCM tradition. It’s that the DIY and semi-pro woodworking community has lost the sense of traditional craftsmanship and utility that defined the early days and inspired the movement. At the short-lived Bauhaus in Germany, students learned how to use traditional joinery to create innovative designs, while also blending media such as woodworking, metalworking, and textiles to design and build furniture and objects that made you feel at home and comfortable. Again, it’s hard to explain, but what goes by MCM today among many woodworkers strikes me as appealing a little too much to the sleek and edgy (sharp angles were all but absent in early MCM) and not enough to the goal of simply paring things down to their purest, most essential elements.

I’m being an annoying purist here, but no apologies for that. The ethos I often repeat about blending traditional and modern methods was the essence of mid-century modern furniture and design. It wasn’t about being flashy. It was about the true, the good, and the beautiful, which, btw, are the three pillars of philosophy. Maybe more on that at a later date.